This toolkit will serve as a guide for the WSLC’s legislative program as we continue to build power for all working people and integrate racial equity into all that we do.

This WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit is also available in a printable 22-page PDF format.

Labor Family,

The Constitution of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO (WSLC) guides our work and charges us to “combat resolutely the forces that seek to undermine the democratic institutions of our nation and to enslave the human soul.” The preamble continues by calling on us to “strive always to win full respect for the dignity of the human individual whom our unions serve.” Institutional racism and systemic policies that disadvantage Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC*) are such forces. As the elected leaders of the WSLC, which is formed of more than 600 local unions, organizations, and councils representing over 1/2 million working people in Washington State, it is our duty to fight for racial and economic justice.

We are charged to win gains and power for working people. We recognize that the fate of all workers, regardless of color or background, are interconnected and that we either rise together or fail. Racism is a system of oppression designed to divide the working class so the wealthy elite can consolidate their wealth and power at the very top. We will win when all workers are recognized and empowered. By acknowledging that racial justice and economic justice are inextricably linked, we commit to sharing the responsibility for racial justice and equity, and actively work together to achieve the transformation we aspire in our unions, workplaces and in the community.

Since 2015, the WSLC has developed and run anti-racist training, designed for rank-and-file membership to grow collective consciousness about our role fighting white supremacy and building a more inclusive labor movement for all workers. Resolutions passed by WSLC affiliates guide our work and lay plain our trajectory:

● Our history: “race and the course of organized labor are inextricably bound and have been since workers made their first appearance on the shores of North America”

● Our current challenge: “organized labor needs to develop a robust counter narrative to that offered by right-wing populism.”

● The work we must take on: “unions need to integrate racial justice into every area of their organization… to wholeheartedly combat the divide and conquer strategy of our enemies.”

The WSLC’s 2019 Resolution on Race and the Labor Movement 3.0 called on us to create additional and supplemental modules to further expand our Race and Labor work. This toolkit — the “WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit” — is an expansion of our program, made possible by the engagement and support of the WSLC’s affiliated unions commitment to racial and economic justice and the growing necessity to examine labor’s work in the legislative space. By examining our labor policies to ensure they promote and advance racial equity, our unions, workplaces and communities will be transformed for the betterment of all people.

The work we pride ourselves on as a labor movement – better wages, benefits and working conditions – they all start with policy. The procedures, regulations and practices within our collective bargaining agreements are policy. And while this toolkit examines policies as laws, our work to examine our policies extends beyond just the legislative policies we create and support. It is our hope that this toolkit and the practice of engaging the voices, leadership, needs, and power of Black, Indigenous and People of Color will extend beyond legislative policy and permeate our unions halls and the decisions we make daily to strengthen the labor movement.

Black workers, who represent 13.5% of union members, are the most likely of any racial demographic group to be union members. The union advantage is greater for Black and Latinx workers, who are paid 13.7% and 20.1% more, respectively, when they belong to a union. While people of color will become a majority of the American working class in 2032, the decline of unionization has played a significant role in the expansion of the racial wage gap over the past four decades, and an increase in unionization would help reverse this trend. In a 2020 Report by the Washington State Labor Education Research Center, we learned just under half of the state’s workforce (1.4 million people) were deemed “essential” yet worked in high-hazard occupations during the COVID-19 pandemic. These workers are disproportionately Black, Indigenous and people of color without the protections of a union contract. This is our moment. union favorability is at an all time high. If we are to seize this opportunity and grow our unions, the intersection of racial and economic justice is where we begin.

It is not lost on us that racism continues to be promoted by corporations and extremist antilabor and anti-democratic forces as a means to divide working people and weaken our political and economic power with the aim of imposing austerity, the destruction of unions and the crippling of all democratic institutions and rights. Racism is corrosive to both the labor movement and democracy. Voter suppression and the attacks on voting rights are deliberately racist and an attempt to silence the voices of people of color. In our communities, we must defend voting rights and in our union halls we must center the voices and needs of people of color in our fight for racial and economic justice.

As we work on policy and work to promote a racial equity lens in the full policy process, we have an opportunity to reexamine the old-age adage that “a rising tide lifts all boats.” If we are to strengthen our labor movement and ensure it is a movement that all working people want to join, we must do the work of (1) promoting policy that eliminates current racial divides, (2) consider the impacts of our policies on BIPOC, (3) center the voices of BIPOC in policy creation, (4) consider the barriers to policy that creates more equitable outcomes, and (5) mitigate the negative impacts of past policies on BIPOC. That is where policy work begins and this toolkit invites us as a labor movement to move beyond broad-based policy approaches to entirely racially equitable policies that provide effective ways to eliminate current racial divides.

This pandemic and the wave of heightened union activism has ignited a fire in us all. As workers strike, walk off the job, and take to the streets to demand our voices be heard, we are reminded of our power. Working people joining together in solidarity with co-workers of all colors and backgrounds won increased wages, strengthened safety protections, better benefits, and a fair return on our work. There is dignity in all work and working people have demanded and are winning respect. As we grow and build a stronger anti-racist labor movement, more workers will win. Our power lies in our ability to come together in union – across race and place – because the union makes us strong.

Solidarity Forever,

President Larry Brown and Secretary Treasurer April Sims

January 2022

This WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit has been adapted to meet the needs of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO for the purposes of advancing racial equity in our labor policy. The tool and corresponding racial equity principles are based on the original Racial Equity Scorecard, previously designed and authored by Marlysa D. Gamblin, founder and CEO of GamblinConsults, a racial equity and anti-racist consulting firm for Bread for the World Institute to help policymakers promote racial equity. All rights reserved, GamblinConsults.com.

This WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit has been adapted to meet the needs of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO for the purposes of advancing racial equity in our labor policy. The tool and corresponding racial equity principles are based on the original Racial Equity Scorecard, previously designed and authored by Marlysa D. Gamblin, founder and CEO of GamblinConsults, a racial equity and anti-racist consulting firm for Bread for the World Institute to help policymakers promote racial equity. All rights reserved, GamblinConsults.com.

EXPANDING OUR WORK ON RACE & LABOR: PUBLIC POLICY APPROACHES

The WSLC is built on the principle of lifting the voices of working families and harnessing collective worker power to build stronger unions across Washington State, while establishing an independent political voice. Through our legislative program – which centers the issues and voices of working people – we win political power to advance policies that work for working families. As our society adjusts to the presence of Covid-19 during this pandemic, the Legislative team at the WSLC is committed to doing the work to make sure the State Legislature takes proactive steps to help workers secure a better life. By promoting the creation of good jobs, securing reliable benefits, improving how government delivers services, protecting the rights of people on the job, and investing in healthy communities, our Legislature can help ensure that working families can recover.

The WSLC is built on the principle of lifting the voices of working families and harnessing collective worker power to build stronger unions across Washington State, while establishing an independent political voice. Through our legislative program – which centers the issues and voices of working people – we win political power to advance policies that work for working families. As our society adjusts to the presence of Covid-19 during this pandemic, the Legislative team at the WSLC is committed to doing the work to make sure the State Legislature takes proactive steps to help workers secure a better life. By promoting the creation of good jobs, securing reliable benefits, improving how government delivers services, protecting the rights of people on the job, and investing in healthy communities, our Legislature can help ensure that working families can recover.

Organized labor is a mass movement for change built by the working people who power our economy and advocate for our communities. Historically, racism has served to divide working people, fracturing our solidarity and weakening our ability to make gains for all workers. The struggle for racial justice is inherently an economic struggle and is central to the work of the labor movement. As we continue to center racial justice in our work, as laid out by our Race and Labor resolutions, we must ensure that our work in legislative advocacy and our work to advance labor policy promotes racial equity.

Racial equity is a process and an outcome. As an outcome, racial equity focuses on achieving equal outcomes for Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC*) relative to their white counterparts. As a process (to achieve this outcome), racial equity is about centering, affirming and respecting the leadership, perspectives, experiences and power of BIPOC from the beginning through the end of the process. (1)

To honor the charge of our Constitution in our legislative work “to combat resolutely the forces that seek to undermine the democratic institutions of our nation and to enslave the human soul” and advance racial equity, the WSLC legislative team has developed this Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit. This customized tool will help the United Labor Lobby (ULL), a statewide coalition of union and advocacy groups, promote racial equity in policy creation. In addition to the tool and toolkit, the WSLC has created a series of workshops to establish a baseline for racial equity concepts in policy.

This toolkit will serve as a guide for our legislative program as we continue to build power for all working people and integrate racial equity into all that we do.

PRINCIPLES TO PROMOTE RACIAL EQUITY

Building power as a labor movement requires that all working-class people are supported. Promoting a racial equity lens in the full policy process – ideation, design, advocacy, implementation and evaluation – is an important step to eliminate racial divides in the state of Washington and to strengthen the collective power of our entire movement. Throughout the process of creating this toolkit we prioritized the voices, leadership, needs, and power of Black, Indigenous and people of color in the labor movement in Washington State. Their leadership, along with our Racial Justice committee and United Labor Lobby, helped shape and develop an understanding of what support our affiliates need to promote racial equity in labor policy.

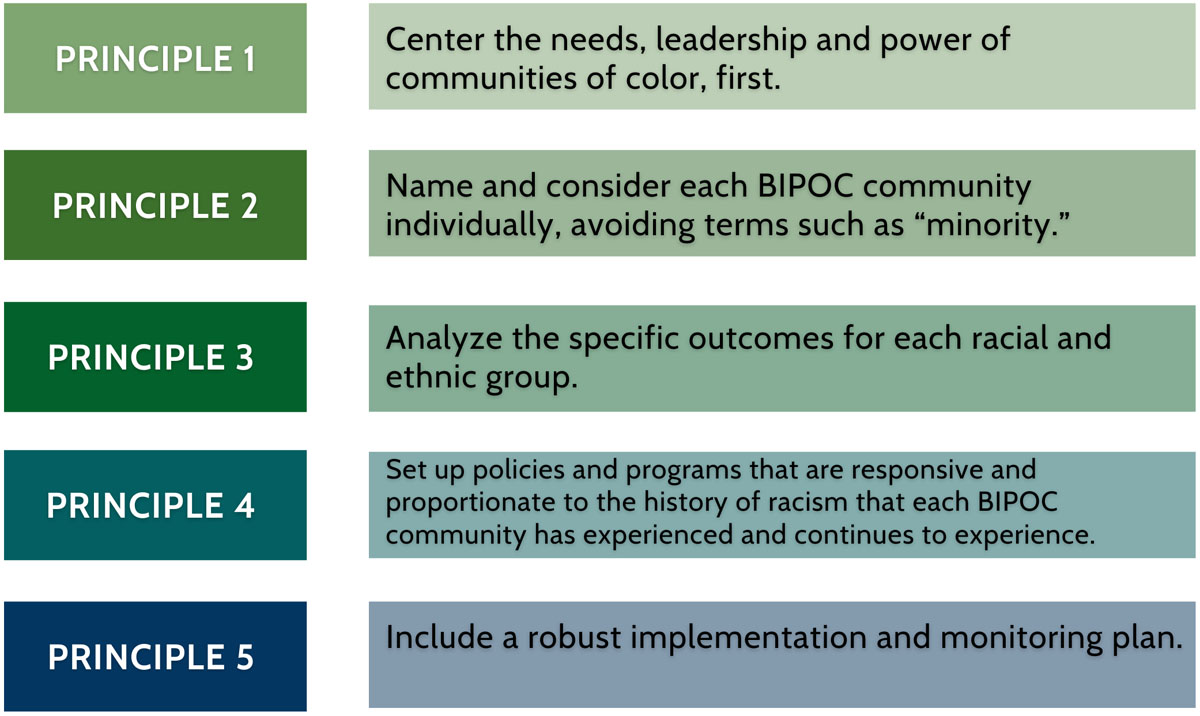

These five principles will help promote racial equity in policy, both as an outcome and as a process. (2)

Principle 1: Center the needs, leadership and power of communities of color, first.

Principle 1: Center the needs, leadership and power of communities of color, first.

Good policy is built through collaboration and careful preparation. To promote racially equitable policies that build worker power, this process must center BIPOC communities and leadership throughout its five stages: (1) Ideation — when an idea is first considered; (2) Design — when that idea is outlined as a policy; (3) Advocacy — when a campaign is underway to pass the policy into law or rule; (4) Implementation — when policy is implemented as a program or law; and (5) Evaluation — when the impact of the program or law is assessed.

As a process when an idea is first raised, before the policy design is complete, ask these questions:

● Where are ALL of the BIPOC communities, including the BIPOC staff working in our own institution and the BIPOC rank-and-file members who are directly impacted by this issue?

● What are the anti-racist mechanisms for identifying all BIPOC communities impacted by this issue and ensuring that no BIPOC community is excluded from the beginning stages conversations?

● How can we co-create a way of engaging alongside BIPOC staff, BIPOC rank-and-file members and institutions led by BIPOC, in a racially equitable way, BEFORE making decisions?

● What systems are in place that grant BIPOC staff, BIPOC rank-and-file members and BIPOC community-led efforts and institutions real decision- making power instead of participatory engagement, before we begin the ideation phase?

● What systems are in place that ensure that BIPOC staff, BIPOC rank-and-file members and BIPOC community-led efforts and institutions are being treated as FULL PARTNERS, before we begin the ideation phase?

● How am I and my institution respecting the leadership of BIPOC staff, BIPOC rank-and-file members and BIPOC community-led efforts and institutions during the ideation phase? Whose ideas are being respected? Heard? Centered? Written down? Finalized?

● How am I and my institution using, centering, and prioritizing the research, data and scholarship of BIPOC staff, BIPOC rank-and-file members, BIPOC community-led efforts and institutions and other BIPOC experts in our analysis and how it is impacting BIPOC communities?

Principle 2: Name and consider each BIPOC community individually, avoiding terms such as “minority.”

Principle 2: Name and consider each BIPOC community individually, avoiding terms such as “minority.”

Each BIPOC community has its own history, experiences and challenges. Name Black communities, Indigenous peoples, non-white Latino/a/x, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders and Asian American communities separately. To the extent possible, do the additional steps of naming communities more specifically. So, instead of saying “Black communities in Seattle,” specify several-generation Black American communities, Ethiopian communities and Nigerian communities. While all of these groups are part of the Black diaspora, they have unique historical traumas rooted in anti-Black racism, as well as different present-day experiences in the U.S. After naming each community, take steps to identify how the existing policy or proposal would impact members of each community.

As a process, ask these questions:

● Am I or my institution using “minority” or other like terms that reinforce racial oppression?

● Am I or my institution using language that groups all BIPOC communities together instead of individually naming them?

● Am I and is my institution naming each racial community the way they have expressed wanting to be identified?

As an outcome, as you are designing the policy, ask these questions:

● Who are all the communities impacted by this, by race? Note that if Principle 1 was practiced well, then you would have already identified all the communities impacted by this who need to be lifted up and named.

● Can we go further to name each specific community within these racial groups?

Principle 3: Analyze the specific outcomes for each racial and ethnic group.

Principle 3: Analyze the specific outcomes for each racial and ethnic group.

The experiences and outcomes of each BIPOC community are different. Data helps us understand how policies impact our communities. “Disaggregated data” — data broken down into smaller, more specific categories — helps us understand impacts to specific communities. For example, a data set might refer to “Asian/Pacific Islanders” which includes people with heritage in at least 40 nations who have different economic, social and political experiences in the U.S. Instead of “Asian/Pacific Islander,” disaggregated data might identify specific groups such as Vietnamese, Marshallese or Chinese. Disaggregated data is important, but still such categories may not provide a clear picture of racial inequities playing out.

As an outcome, as you are designing and/or analyzing the policy, ask these questions:

● How does each racial and ethnic group fare with each outcome that is being measured (i.e. hiring rates, pay rates, unemployment rates, union representation, etc.)? What are these racial outcomes, cross tabulated by ethnicity? Vice versa? While these outcomes can certainly be quantitative, we also want to look at qualitative outcomes. For example, how are Vietnamese workers experiencing discrimination during the implementation phase of this policy?

● What are the reasons for the outcomes experienced by each racial and ethnic group? As mentioned in Principle 2, each BIPOC community has a different historical trauma (refer to the text box above for definition). Decisions about adopting solutions should be rooted in an understanding of why the various circumstances and outcomes have occurred. Otherwise, the solutions will not adequately address the impact of specific racial inequities on the problem.

● What is the disaggregated racial and ethnic makeup of the population that this program or policy serves (if you are working with an existing policy) or seeks to serve (if the policy is new)? Understanding the scope of the communities and individuals involved is important to identifying any gaps between the policies you are working on and the actual needs of the community. Note that implementing Principle 1 well will help guide what the actual needs of the community are because the community would be driving the process.

● What is, or is expected to be, the impact of this program or policy on each named community? While it may prove challenging to determine many details on these impacts, it is important to collect and synthesize as much disaggregated information as possible to help you understand which targeted community-specific changes need to be incorporated to help solve the problem and ensure equal outcomes for all communities.

● What does this impact mean in terms of widening, maintaining, narrowing or eliminating current racial divides between each named community and their white counterparts?

Principle 4: Set up policies and programs that are responsive and proportionate to the history of racism that each BIPOC community has experienced and continues to experience.

Principle 4: Set up policies and programs that are responsive and proportionate to the history of racism that each BIPOC community has experienced and continues to experience.

Not understanding why and how to address specific historical traumas is a common reason that well-intentioned initiatives fail to promote racial equity. Most policies and programs treat all communities the same, regardless of the different experiences and outcomes faced by specific racial communities. Instead, responses should be community- and circumstance-specific.

As a process, ask these questions:

● What is the racial historical trauma related to this issue for each named community?

● Am I and my institution taking the lead on researching and analyzing this racial historical trauma? Or am I and my institution putting the responsibility of this labor on our BIPOC staff, BIPOC rank-and-file members and other BIPOC partners?

As outcomes, responses should be community-specific, community-driven and result in the elimination of current racial divides:

● What is the disaggregated data of each named community, as explained in Principles 2 and 3? This will help determine how much targeted support each BIPOC community needs to achieve equal outcomes.

● What is the historical trauma for each named community? This should be asked in the process section for Principle 4. Asking this will inform not only how much support each community needs to achieve equal outcomes but will also inform HOW it should be provided to account for a history of government mistrust, racial oppression, exclusion, etc. In most cases, the policy should be implemented by and for each named community.

● What is the racial wealth divide for this named community? A significant way that racial historical trauma continues to exist is through the racial wealth divide. In order to achieve equal outcomes by race, it is necessary to name the extent to which the racial wealth divide affects each BIPOC community, and make sure the policy provides support to each community at a level proportionate to the racial inequity they experience.

Principle 5: Include a robust implementation and monitoring plan.

Principle 5: Include a robust implementation and monitoring plan.

While policy ideation and design stages are important, implementation and evaluation stages that promote racial equity are equally important. When BIPOC experts co-create the terms from the beginning (see Principle 1), they help inform the implementation and evaluation stages as well. When everyone is informed and involved from the beginning, it makes for a better process AND outcome.

As a process, ask these questions:

● In concert with Principle 1, did the named BIPOC communities co-create the process for designing the implementation and evaluation process?

● Did they have real decision-making power in the final implementation and evaluation decisions, before the policy was passed into law?

● What was my role and my institution’s role in standing in solidarity with the named BIPOC communities and making sure that they shaped the implementation and evaluation stages, took the lead on these stages once the policy was passed into law and received resources directly (if applicable)?

As an outcome, ask these questions:

● Based on the expertise and scholarship of BIPOC communities (from Principle 1) and my own analysis of racial historical trauma (from Principle 4), is the policy sufficiently resourced for effective implementation? Does this policy have sufficient resources assigned to enforcing anti-racism at the individual and institutional levels?

● Does this policy have systems in place to hold individuals and institutions accountable who are identified as maintaining or exacerbating racism?

● Are there any processes for reporting racism? Have these systems been co-created with BIPOC experts, including staff and rank-and-file members? What are the systems of care and protection for the BIPOC individuals who report?

● Are BIPOC entities that directly serve their communities, and other BIPOC experts with lived and/or scholarly expertise, assigned to co-lead the implementation and evaluation processes? Do they have real decision-making power or are they limited as implementers only?

● How are resources determined and allocated? For example, is it through a grant that requires a request for proposal (RFP)? This option tends to reinforce racial inequities because of the racial wealth divide present among many BIPOC organizations who may not have a grant writer. Maybe the process is through a grant application that specifies eligibility based on whom an institution serves? In cases like this, resources often go to white-led efforts instead of efforts led by named BIPOC communities who are directly impacted. Are resources determined based on eligibility criteria of not only serving BIPOC communities but also being led by named BIPOC communities directly impacted by the issue? How can we ensure that allocated resources are racially equitable?

● By whom are these resources determined and allocated? If Principle 1 was fully implemented, then named BIPOC communities centered from the beginning of the process would have shaped this process.

● Are these resources given directly to BIPOC entities? Or are they given to white-led institutions and efforts that then subcontract or work with BIPOC communities? The latter reinforces racial inequity. Are BIPOC entities/BIPOC communities given the amount of resources they need to eliminate the current racial divides?

● Does the policy outline a racially equitable implementation plan and plan to evaluate?

A Look at Historical Policies, Their Effects and the Need for Anti-Racist Policies Today

The foundation of our work on Race & the Labor Movement understands that race, rather than being a biological construct, is a political-social construct devised by the wealthy elite to keep working people from recognizing their common struggle and uniting against their oppressors. As long as people believe that some folks are superior and some are inferior, then treating people differently and codifying those differences in laws, customs, practices and culture gives rise to the notion that we are racially different and that races can and should be treated differently. Some examples of how this shows up in policy are below, all excerpts from “Racial Wealth Gap Learning Simulation, Policy Packet” by Marlysa Gamblin for Bread for the World Institute (unless otherwise noted).

The Social Security Act, enacted in 1935, was intended to provide a safety net for workers, particularly those suffering during the Great Depression. However, the newly-created Social Security system excluded farmworkers and domestic workers—who were predominantly Black, Latino/a/x, and Asian—from receiving both old-age and unemployment insurance. Sixty-five percent of Black Americans were ineligible for Social Security unemployment insurance at the time the law went into effect, even though Black Americans and other people of color were twice as likely as white Americans to face hunger or poverty during the Great Depression. The unemployment rate among Black Americans was also twice as high as the national average. Among female-headed households, Black women were twice as likely as white women to be unemployed. In the north, unemployment rates were as much as 80 percent higher for Black Americans than white Americans. (3) When national unemployment during the Depression is disaggregated by gender, unemployment for Black men ranged from one-third higher to double that of white men, and Black women were between two and four times as likely to be unemployed than white women.

The Social Security Act, enacted in 1935, was intended to provide a safety net for workers, particularly those suffering during the Great Depression. However, the newly-created Social Security system excluded farmworkers and domestic workers—who were predominantly Black, Latino/a/x, and Asian—from receiving both old-age and unemployment insurance. Sixty-five percent of Black Americans were ineligible for Social Security unemployment insurance at the time the law went into effect, even though Black Americans and other people of color were twice as likely as white Americans to face hunger or poverty during the Great Depression. The unemployment rate among Black Americans was also twice as high as the national average. Among female-headed households, Black women were twice as likely as white women to be unemployed. In the north, unemployment rates were as much as 80 percent higher for Black Americans than white Americans. (3) When national unemployment during the Depression is disaggregated by gender, unemployment for Black men ranged from one-third higher to double that of white men, and Black women were between two and four times as likely to be unemployed than white women.

Subprime loans are loans that carry higher interest rates than prime loans, which are more desirable since their interest rates are lower. Often, subprime loans are the only loans that people considered at higher risk of defaulting can qualify for. These “high risk” borrowers generally have low incomes and/or poor or limited credit records. Borrowers with subprime loans ultimately pay more for their homes, since they pay higher interest rates throughout the mortgage period. The higher monthly interest rate also increases the risk of foreclosure. Being approved disproportionately for subprime rather than prime loans meant that Black Americans paid a higher percentage of their income toward their mortgages than their white counterparts, leaving them less money for food, savings, and other needs. Subprime loans devastated Black American communities and eroded wealth that had been accumulating. Many gains that had been made were eliminated. “At its peak, one out of every five mortgages in the country were in this mold… $19 trillion in lost wealth. Pensions, home equity, savings. Eight million jobs vanished. A home-ownership rate that has never recovered.” Learn more about subprime loans, predatory lending and impacts on working people in the video “Racism has a cost for everyone” TED Talk by author Heather McGhee:

![]()

Currently, there are more than six million people who are barred from voting under laws dating back 150 years. As early as 1792, some states amended their constitutions to disenfranchise people convicted of crimes. Some state documents stated explicitly that the purpose was to “establish white supremacy.” The Communications Workers of America published a guide for labor activists, “Reversing Runaway Inequality,” which points out after the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, guaranteeing Black men the right to vote, white supremacists came up with a score of ways to disenfranchise them: “Poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses and cross burnings were effective weapons in this campaign [to keep Black male citizens from voting]. But statutes that allowed correctional systems to arbitrarily and permanently strip large numbers of people of the right to vote were a particularly potent tool in the campaign to undercut (Black) American political power.” If Black Americans had not suffered disenfranchisement, it would have been much less likely that legalized discrimination in the workforce, school, financial systems, and other institutions would have been allowed to continue. Undermining efforts that are meant to end discrimination in voting enables the wealth gap to further expand.

WSLC RACIAL EQUITY & POLICY TOOL

We know there can be no economic justice without racial justice. In our work to become an anti-racist labor movement we must do the work to create policies and practices that distribute resources, power and opportunity to all working people in a just and equitable way.

We know there can be no economic justice without racial justice. In our work to become an anti-racist labor movement we must do the work to create policies and practices that distribute resources, power and opportunity to all working people in a just and equitable way.

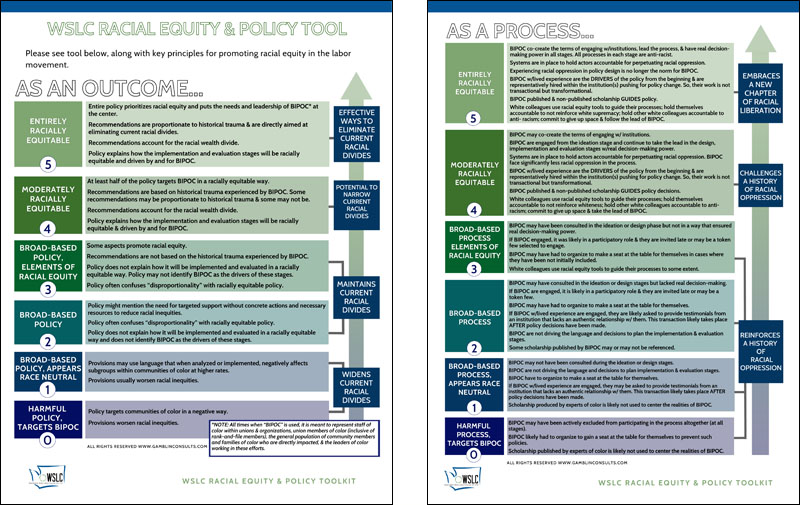

The WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Tool — which is posted separately online here and appears on Pages 15-16 of the printable PDF version — assesses how successfully a proposed or existing policy promotes racial equity. The policy can be assessed on a scale of 0 (“harmful policy” capable of widening racial inequities) to 5 (“racially equitable” in each aspect), both as an outcome and a process.

This tool is for policymakers, policy analysts, rank-and-file advocates and anyone who supports policy that can eliminate current racial divides. Most policies in the labor movement tend to be broad-based, meaning that the policy benefits people in a broad way, but may not do the additional work of providing targeted support to eliminate current racial divides. Many broad-based policies could be made more racially equitable by (1) applying this ranking tool to evaluate each part of the policy; (2) making recommendations that acknowledge and address the deep origins of racism throughout U.S. history; and (3) centering the needs, leadership, and power of BIPOC in every stage of the policy process.

See the WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Tool.

SUMMARY OF QUESTIONS

The WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit encourages us to consider the following questions:

![]() To what extent does the policy prioritize the needs and leadership of all BIPOC communities, including the BIPOC staff working in our own organization and the BIPOC rank-and-file members who are directly impacted by this issue? (Principle #1)

To what extent does the policy prioritize the needs and leadership of all BIPOC communities, including the BIPOC staff working in our own organization and the BIPOC rank-and-file members who are directly impacted by this issue? (Principle #1)

![]() Which specific racial and ethnic groups are impacted? How and to what extent does the policy address historical trauma experienced by each racial and ethnic group? Is proportionality considered? (Principles #2 and #3)

Which specific racial and ethnic groups are impacted? How and to what extent does the policy address historical trauma experienced by each racial and ethnic group? Is proportionality considered? (Principles #2 and #3)

![]() How and to what extent does the policy address the racial wealth divide for each named BIPOC community? Is proportionality considered? (Principle #4)

How and to what extent does the policy address the racial wealth divide for each named BIPOC community? Is proportionality considered? (Principle #4)

![]() Does the policy outline a racially equitable plan to implement and evaluate the policy? (Principle #5)

Does the policy outline a racially equitable plan to implement and evaluate the policy? (Principle #5)

Practice Using the Tool: Evaluating Federal Stimulus Checks

At the bargaining table, in our workplaces and in policymaking spaces, we see that racism is a system of oppression designed to divide the working class so the wealthy elite can consolidate their wealth and power at the very top. In the public policy arena, this division and harm has been propagated and compounded across centuries. Policies that do not explicitly dismantle racial divides undermine the power of working people of all backgrounds. As the labor movement works to improve conditions for workers via public policy, we can be even more effective by designing and advancing policies that challenge and eliminate racial divides.

This toolkit can help the labor movement assess how and to what extent policies impact racial equity. Below is an example of how we can apply the toolkit to a policy.

$1200 Stimulus Checks for Covid Response: April – May 2020

In response to the onset of the health and economic impacts of the novel coronavirus, Congress authorized three economic impact payments, commonly called stimulus checks.

In response to the onset of the health and economic impacts of the novel coronavirus, Congress authorized three economic impact payments, commonly called stimulus checks.

The first check was intended to reach a broad swath of Americans in need of financial support as many work sites – including schools – shut down for safety, and increasing numbers lost income due to illness.

“Starting in March 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) provided Economic Impact Payments of up to $1,200 per adult for eligible individuals and $500 per qualifying child under age 17. The payments were reduced for individuals with adjusted gross income (AGI) greater than $75,000 ($150,000 for married couples filing a joint return). For a family of four, these Economic Impact Payments provided up to $3,400 of direct financial relief.”

Question 1. To what extent does the policy prioritize the needs and leadership of all BIPOC communities, including the BIPOC staff working in our own organizations and the BIPOC rank-and-file members who are directly impacted by this issue? (Principle #1)

The policy outcome does not center the needs and leadership of BIPOC workers. This policy appears race-neutral and broad-based, but implementation widens current divides.

Question 2. Which specific racial and ethnic groups are impacted? How and to what extent does the policy address historical trauma experienced by each racial and ethnic group? Is proportionality considered? (Principles #2 and #3)

This policy is citizenship-based: only U.S. citizens and U.S. resident aliens are eligible to receive stimulus payments.²⁷ This means that undocumented people, for instance, are excluded from this financial support. While immigration status is not equivalent to racial categories, a history and practice of race-based immigration policy means that undocumented people are disproportionately people of color (Learn more in the WSLC “Race to Labor” publication). A policy that excludes undocumented immigrants widens current racial divides.

Question 3. How and to what extent does the policy address the racial wealth divide for each named BIPOC community? Is proportionality considered? (Principle #4) Does this policy increase, maintain, decrease or eliminate racial wealth divides? This policy ultimately increased racial divides:

● The implementation creates delays for people most in need of the relief promised by the policy: People who file taxes with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and provide the IRS bank account details for direct deposit are the first to receive checks, while others received the stimulus check months later.

○ Four million family households in the U.S. are headed by Black American women – and nearly 1 in 4 of those households live below the poverty level. Many people below the poverty level do not file taxes.

○ One third of Black American men will serve time in federal prison during their lifetimes. Once out of prison, people have a harder time finding employment and housing due to their arrest records – impacting their ability to file taxes as well.

● Having a bank account made it easy to receive a check. However, access to a bank account is not equitable in our country.

○ Un- or underbanked rates are higher for Black and Indigenous populations and higher for all BIPOC compared to white people.

○ In 2017 the FDIC published a national study that included disaggregated data by race, gender, age, disability and other areas. In this study, younger households, Black and Hispanic households remained substantially higher than the overall unbanked rate.³⁰

○ If people did not have bank accounts for direct deposit, they could receive a payment in the mail. People without a home address or in transition faced potential challenges.

Question 4. Does the policy outline a racially equitable plan to implement and evaluate the policy? (Principle #5)

No, the policy did not include a plan for racially equitable implementation – this oversight deepened inequities for Black women, Black and Indigenous communities, undocumented people and people who are not yet residents.

The policy did not include a plan to evaluate the impacts on specific racial and ethnic groups.

Evaluating Federal Stimulus Checks: Using the tool this policy would be rated at a 0.5 or a 1 (one). This policy did not center the needs of BIPOC workers, and is not informed by historical traumas experienced by racial and ethnic groups. This policy did not address the racial wealth divide, and in some instances widens the racial wealth divide because of who could and could not receive stimulus checks. Additionally, this policy did not include a plan for racially equitable implementation. This example focused on key themes of the tool; however, we encourage a more comprehensive use of the tool, guiding principles (including in-depth demographic analysis) and questions to consider while evaluating our work ahead.

Our Call to Action: The WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit serves as a guide to evaluate every step of the policy process – ideation, design, advocacy, implementation and evaluation. Now that we practiced applying a racial equity lens in policy, it is time to carry the work forward. Each legislative session in Washington state is an opportunity to lead with racial equity and design policies that center racial and economic justice. We invite you to join in this work to move beyond broad-based policy approaches to racially equitable policies that solidify our commitment to solidarity and build true power for all working people.

THANK YOU

We are excited about the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit. The toolkit significantly advances our work on race and the labor movement, broadening our capacity and infrastructure in policy. We offer the WSLC Racial Equity & Policy Toolkit to our affiliates and partners here in Washington, with the hope that its impact goes beyond working people in our state and beyond our legislative work.

This toolkit isn’t possible without the affiliates who supported the project and the people who joined us on this journey over the last six months.

From the beginning, our methodology prioritized the voices, leadership, needs, and power of Black, Indigenous and People of Color in the labor movement in Washington State. Our learning started with forming listening sessions with WSLC Constituency Groups of Color and the WSLC Racial Justice Committee. We are proud of this intentional process to promote racial equity principles in the design of the project and believe that the content in this toolkit is much stronger as a result.

In addition, the cross-racial solidarity shown by the WSLC Executive Board, affiliated union leadership and the United Labor Lobby through active participation in listening sessions and subsequent workshops was integral to the development of this toolkit.

To our partner in this work, our consultant Marlysa D. Gamblin, founder and CEO of Gamblin Consults (hello@gamblinconsults.com), a racial equity and anti-racist consulting firm, thank you so much. We honor your work and the creation of the original “Policy Ranker” and “Racial Equity Scorecard”. Your expertise and knowledge helped to guide us through this process as we set out to strengthen our racial equity work. You are

To our partner in this work, our consultant Marlysa D. Gamblin, founder and CEO of Gamblin Consults (hello@gamblinconsults.com), a racial equity and anti-racist consulting firm, thank you so much. We honor your work and the creation of the original “Policy Ranker” and “Racial Equity Scorecard”. Your expertise and knowledge helped to guide us through this process as we set out to strengthen our racial equity work. You are

appreciated.

In solidarity and love!

REFERENCES

*NOTE: All times when “BIPOC” is used, it is meant to represent staff of color within unions and organizations, union members of color (inclusive of rank-and-file members), the general population of community members and families of color who are directly impacted, and the leaders of color working in these efforts. As our language constantly evolves, we defer to communities’ definitions of themselves.

1. Definition from Marlysa Gamblin of GamblinConsults.

2. Racial equity principles have been adapted by Marlysa Gamblin of GamblinConsults for the purposes of this toolkit. The original principles are featured on the Racial Equity Scorecard that can be found at bread.org/racialequity.

3. Trotter, Joe W. “African Americans, Impact of the Great Depression on.” Encyclopedia of the Great Depression, edited by Robert S. McElvaine, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2004, pp. 8-17. U.S. History in Context.